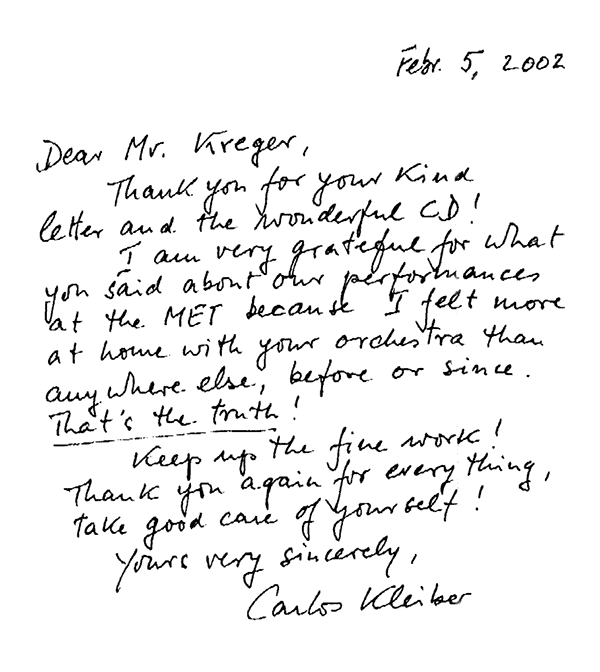

“I felt more at home with [the Metropolitan Opera] Orchestra than anywhere else, before or since. That’s the truth!”

Carlos Kleiber, the eccentric and reclusive conductor who died in 2004 at the age of 74, was a fabled perfectionist who was known as much for the rarity of his appearances as for the brilliance of his interpretations. Cellist James Kreger, who had the opportunity to experience Kleiber’s genius firsthand, reflects on what made this great artist so remarkable and uncovers some of the mysteries of what it means to be a musician. (This tribute originally appeared in The Juilliard Journal, November 2004.)

Having played in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra under many conductors, it was my great fortune to make music with Carlos Kleiber when he conducted four operas at the Met in the late 1980s and early ’90s: La Bohème, La Traviata, Otello, and Der Rosenkavalier. These were, and no doubt will remain, some of the most memorable moments of my life. I hasten to add, many of the world’s greatest conductors were also in attendance to witness what were rare occasions indeed, since Carlos Kleiber hardly ever conducted. Among them was Leonard Bernstein (whose front-page New York Times obituary was headlined “Music’s Monarch”). This “monarch” of music told his New York Philharmonic colleagues: “I have just heard the greatest living conductor in the world—Carlos Kleiber. You owe it to yourselves to hear him, and it’s too bad if you have to work on a night when Carlos Kleiber is conducting.”

There are a number of qualities that made Carlos Kleiber different from other conductors. The unique combination of these made him special. For one thing, he tended to trust the orchestra more than most conductors. Like other conductors, he might work in tremendous detail on certain spots—such as the final moments of the first act of Otello, where he wanted the clarinet to predominate just so over the orchestra in pianissimo, creating a very special color, or the opening of the final act, with the plaintive English horn solo. And then there was the prelude to the final act of Traviata, where he worked intensively to create multi-layers of color and pianissimi in the first violins, while maintaining the thread of a plangent, vulnerable, cantilena line. Moments such as these serve as benchmarks and indeed give new meaning to the term “inevitability” in music. In other spots requiring ironclad internal ensemble or intonation, which many conductors spend time drilling, Kleiber was content to trust the orchestra. Once, in a rehearsal, when we were so intent on following him, he told our concertmaster at that time, Raymond Gniewek: “Let me follow you.”

When things didn’t go to his satisfaction, his conducting became more emphatic, as often happens with other conductors. Yet with Kleiber, the orchestra seemed to have an extrasensory awareness, and this created more tension and excitement as the level reached higher and higher. While his commitment to the score and his charisma were unquestionable, other conductors have these qualities. Yet Kleiber was very much in the moment, never satisfied with the status quo, always looking for a different way, perhaps a better way, to do the same passage. This quality of looking deeper into the score, and acting upon it at a moment’s notice, put the orchestra on its toes. He projected passion and total involvement, and the orchestra wanted to reciprocate. Following one of the early Bohème performances, how ashen his face appeared—as if he had lived the story of the opera, and especially the death of Mimi.

Kleiber conducted the phrase instead of merely beating time. His baton conveyed a palette of colors and nuances, while never losing the sense of pulse. His use of his hands was beautiful and expressive. He paid tremendous attention to detail yet, at least for this listener, he never lost sight of the big picture: Listening to his recording of the Brahms Fourth Symphony (one of 10 works Kleiber recorded for Deutsche Grammophon) is riveting; each movement seems to interconnect, as if it all were one huge arch while constantly building up to the finale. Kleiber had complete and absolute independence of his hands: If necessary, he could conduct one meter in one hand and another in his other hand. Often he would conduct different phrasing in each hand, depending upon the particular voice or instrument he wanted to illuminate.

He had an uncanny ability to realize simultaneously each individual character in an operatic scene. For instance, in the first act of Rosenkavalier there are many characters onstage, and a lot is going on: Each is singing/speaking a different line—often in a different rhythm, often overlapping—sometimes arguing, interrupting each other, expressing different points of view, emotions, etc. Most conductors in a similar situation, where the scene is complicated and there are many characters onstage, would indicate a basic pulse, in order to keep everything from falling apart, and rely on the prompter and the singers to do the rest. Not Kleiber. With him, you always had the sense that all the voices/roles onstage and in the pit, each with its own distinct character, were being channeled simultaneously through him. You felt as if he was living each character at the moment and at the same time as the others. Often he would conduct as many different characters onstage and instruments in the orchestra as he had fingers on both hands, all at the same time, flawlessly and effortlessly, throwing out cues with different fingers for each character. But that in itself was not enough, until he could inhabit each one of those characters in addition to everything that was going on in the orchestra. Indeed, he had absorbed the score and the history of the work with such depth that he was inhabiting the psyche of the composer. No doubt many long hours of study went into the preparation of each work he conducted.

With all his knowledge of the score, he seemed disarmingly honest—even humble—about his views on some works, as is often the case with great men. In 2002 we had a brief correspondence. In one of my letters to him I spoke about the performances of Falstaff we were doing at the Met, and how much I loved the opera. In his reply he stated: “Now the Met is doing Falstaff, which is a jewel—more to read and listen to (on grand old recordings) than to see and hear performed I find. A lot of the music is just too beautiful for the situations on stage which, it is, well, ‘accompanying.’ And I could never get up any enthusiasm for the final fugue nor the bits (where they’re beating the old guy) that lead up to it. (My friend Riccardo Muti says I don’t understand what Verdi meant. I guess he’s right.)” Kleiber had great affection for the Met Orchestra. He expressed this in another letter: “I felt more at home with your orchestra than anywhere else, before or since. That’s the truth!”

Making music with Carlos Kleiber was a privilege—when it was happening, you just knew you were in the presence of a powerful, charismatic force, someone guiding you, opening that special door to an experience never to be forgotten. He put us back in touch with those pure emotions and truths, reminding us how lucky we are to be musicians and artists—children of paradise. For me—and this must also be true for the thousands of musicians around the world who have been touched by his genius—when Carlos Kleiber is conducting and we are playing in his orchestra, we don’t feel as if a conductor is inflicting his will upon us, which is usually the case. Rather it is as if we feel exactly the way he does about the music (of course, this is the key!). He is inviting us to join him in an experience that lifts us up and transports us to another time and place: a cosmos of emotion and color. A wall, which normally has two dimensions, becomes a door opening onto infinite dimensions and layers—a universe of worlds, a world of universes. When he held out his arms in a long, cantilena line, they seemed to stretch across the entire orchestra, almost as if he were cradling us. Such moments occurred in the youthful passion of Bohème; the ever-so-vulnerable, fragile pathos of the prelude to the final act of Traviata, with its infinite colors and hues of light and shade; many parts of Otello; and positively in Rosenkavalier where, when the final trio arrives, the orchestra, soloists, and conductor have become as one with the magic and wonder of spinning out that long, soaring, noble line. Making music with Carlos Kleiber, whether in rehearsal or performance, was incomparable. He was in a class by himself. For those of us around the world lucky enough to have shared in this experience, we have been touched forever. —James Kreger